Skeletal radiographs in the neonate

Please note: images that have a white symbol at the top right, such as the Fractured humerus image below, indicates an image gallery that has multiple images - click on the image to open the gallery.

Fractured clavicle

Fractured clavicles are found in up to 2.9% of term infants, more frequently on the right side. They are often silent but may be noticed later when a palpable callous forms at a few weeks of age.

There is often minimal pain apparent, but if the infant is uncomfortable strapping may be all that is required for a few days.

The radiograph to the right shows a linear lucency at the lateral one third of the clavicle.

Fractured humerus

Midshaft (diaphyseal) humeral fractures are often diagnosed at birth when a "crack" or "snap" is heard or felt on delivery of the baby. Clinical signs are variable - the baby may be asymptomatic, may be in pain, or may present with a pseudoparalysis.

Treatment is by immobilisation of the arm by the side with the elbow held at 90°. These fractures usually heal very well over the following weeks.

The images to the right demonstrate a humeral fracture which was suspected at delivery after a difficult extraction. The first image shows the fracture immediately after birth; the second image shows the fracture three weeks later, with good callous formation. The third image shows the fracture 2 months after the initial injury with minimal angulation.

Fractured skull

Skull fractures are generally classified as linear, depressed, or occipital osteodiastasis.

Linear skull fractures, as in the right parietal skull fracture shown at the right, are most common in the parietal region. The exact incidence is difficult to determine although they are reportedly common. The pathogenesis is thought to be from direct compression.

There may be external signs of injury (i.e. haematoma), but significant intracranial complications are rare. Rarely, there is an associated dural tear which may subsequently develop a leptomeningeal cyst.

No specific therapy is indicated, although a follow-up radiograph at several months of age may be useful to show healing.

Depressed skull fractures are most commonly associated with the use of forceps, with the most common site being the parietal bone. They may occur after pressure on maternal pelvic structures. Although rarely associated with epidural or subdural haemorrhage and cerebral injury, a CT scan may nevertheless be indicated. Many depressed fractures are managed conservatively.

Occipital osteodiastasis (separation of the squamous and lateral parts of the occipital bone) may result in intracranial injury (posterior fossa subdural haemorrhage and cerebellar contusion). Typically, infants have been delivered breech and are commonly depressed at delivery. Severe occipital osteodiastasis is associated with a poor outcome.

Osteopenia of prematurity

Poor mineralisation of bone is a relatively common finding in extremely preterm infants, with those under 1000g and less than 30 weeks gestation at most risk. Terminology in the literature can be somewhat confusing, and other terms such as metabolic bone disease and rickets of prematurity have been used interchangeably.

The aetiology is complex, and is relate to both nutritional factors (inadequate intake of minerals), hormones (vitamin D) and to mechanical factors (lack of mechanical stress applied to the bone). Infants most at risk are those who have been very systemically unwell (often with chronic lung disease and receiving diuretic therapy) and have been troubled with suboptimal nutritional intakes.

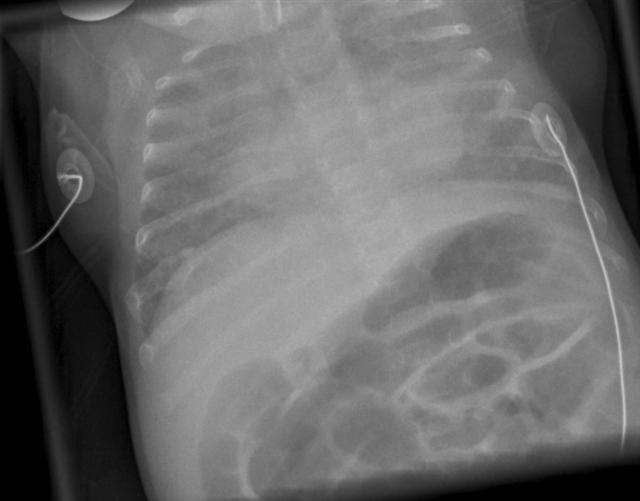

Radiologically, bone mineral density is significantly decreased. This may manifest as "disappearing" bones (such as in the image to the right, where the vertebral bodies and scapulae are barely visible) and in severe cases rib or limb fractures may be seen (in the image to the right, the posterior part of the right 7th rib shows a callous indicating a previous fracture).

Severe osteopenia is rare, probably due to changes in nutritional and other neonatal practices. Some infants will require long-term nutritional supplementation, although there is some evidence that regardless of how osteopenic infants are, bone density improves with age and with adaptation to mechanical requirements of the body.

Osteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis and septic arthritis may occur simultaneously in infants under 1 year of age, due to the unique nature of the vascular supply of the neonatal skeleton (perforating capillaries are present in the epiphyseal plate of long bones and provide a communication between the metaphysis and the joint space). The exact incidence of osteomyelitis and septic arthritis in neonates is not well defined. Common organisms include Staphylococcus aureus, Group B Streptococcus, and Gram-negative enteric organisms, but other organisms are also seen. The origin of osteomyelitis is thought to be haematogenous.

Symptoms are generally non-specific and are often overshadowed by the general condition of the septicaemic child. The baby may present with a pseudoparalysis with reduced movement of the affected limb. Swelling, erythema, and heat over the bone or joint may be present.

Early in the disease, radiographs may be normal. Subsequently, the normal fat markings of deep tissues may be obscured. Cortical destruction is unusual before the second week of the illness, so in the event of Staphylococcal septicaemia a complete skeletal survey should be taken 2 weeks into the treatment (or earlier if there are clinical signs suggesting osteomyelitis or septic arthritis). Clinical resolution precedes radiographic resolution, but some infants are left with significant joint or bone injury.

The images to the right show the serial radiographs of an extremely low birth weight infant with Staphylococcal septicaemia at 1 month of age. He had no clinical signs of osteomyelitis or septic arthritis.

The initial skeletal survey 2 weeks into treatment suggested some lucency in the left proximal humerus with some irregularity of the cortex suggestive of underlying osteomyelitis. A follow-up radiograph 2 weeks later showed clear difference between the right and left humerii. After completion of 6 weeks of intravenous flucloxacillin, there was resolution of the lytic changes in the bone, but some evidence of sclerosis and new bone formation around the proximal humerus.

Osteogenesis Imperfecta

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is a generalised abnormality of bones due to problems with Type I collagen formation. There are at least 4 recognised types, although differentiation between types can be difficult in the newborn period.

Type I OI is most common and the mildest type. There is less collagen than normal, with little bone deformity, although the bones are nevertheless fragile. There may be bluish discolouration of the sclera of the eyes.

Type II OI is the most severe form with improperly formed collagen. Intrauterine fractures are common, and many babies are stillborn or die soon after delivery.

Type III OI also has severe bone deformities. Infants are often born with fractures. Discolouration of the sclerae may not occur. It is compatible with longer life, although people are generally of below-average height, may have skeletal and/or respiratory problems, and brittle teeth.

Type IV OI is moderately severe. Bones are fragile, and the sclerae may be of normal colour. Bone abnormalities are mild to moderate in severity, adults are shorter than average, and may have brittle teeth.

Treatment is largely supportive, with referral to the Orthopaedic, Genetics, and Endocrine services. Medical treatment with bisphosphonates may be indicated.

The images to the right show marked skeletal abnormalities involving bowing of the femurs and tibias, a fracture of the left humerus, and deformity of the right humerus. The chest radiograph demonstrates rib fractures on the left. The skull radiograph demonstrates Wormian bones. The bones appear osteopenic in all films.